Clarion University

Northcentral University, USA

Recived: 27.08.2014

Accepted: 22.10.2014

Original article

Citation: Greene AM. Passing standardized assessments with fading prompts. J Spec Educ Rehab 2015; 16(1-2): 68-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/JSER-2015-0005

Introduction

Through passing No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB), the United

States Federal Government mandated that states meet certain

requirements and develop state assessments to evaluate whether all

students are making progress to a level of proficiency. As a result of

NCLB, the members of the Pennsylvania Department of Education instituted

the Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA), which

evaluates writing based on prompts using a rubric. According to NCLB,

measurable yearly benchmarks, which are referred to as Adequate Yearly

Progress (AYP), must be set to ensure that 100% of students are

performing at a level of proficient by the 2013-2014 school year. The

supporters of NCLB mandate that all students, including those with

learning and intellectual disabilities, perform at a level of proficient

on grade level state assessments with only small group settings as an

accommodation (1–4).These students are expected to meet the same cut

score levels as their nondisabled grade level peers. (4) Students with

learning and intellectual disabilities are by nature at risk for not

meeting a level of proficient due to their common characteristics of

deficits in the areas of computation, strategy development, memory,

self-regulation, motivation, and generalization to state writing

assessments (5–7).

Proficiency on state assessments, such as the PSSA, is a concern for administration, teachers, parents, and students. If AYP is not met funding is reduced and government involvement is instilled within the school districts at varying levels depending on the number of consecutive years the goal is not met (2). Members of the IEP subgroup who have a disability in the area being measured are clearly at a higher risk for not performing at a level of proficiency (8). The issue of passing statewide assessments, such as the PSSA, is becoming even more important since some states already do not permit students who do not pass the test to receive a diploma (9).

Although there has historically been a controversy between advocates for cognitive and behavioral approaches to teaching, NCLB has caused it to be even more pressing. Due to NCLB, teachers need to find the most effective strategy for assisting students with disabilities in passing state assessments. Directly teaching the skills through behavioral techniques has been deemed successful for students with learning and intellectual disabilities due to their common areas of deficits (10–18). Although the research has shown behavioral approaches’ successfulness for students with learning and intellectual disabilities, the advocates for cognitive approaches continue to criticize behavioral approaches for being too rigid (11, 19).

A substantial amount of research on teaching writing over the last several decades has been based on cognitive approaches, such as product, process, and Self-Regulated Strategies Development (SRSD). A large portion of this research was conducted by Graham (20) or replicated his work. Early on Graham (20) has found difficulties in implementing cognitive strategies for students with learning and intellectual disabilities, which included deficits in composition, mechanics, and motivation (20–23). A review of the 30 years of SRSD research allowed researchers to find differences in strategies behavior, writing skills, knowledge, and motivation that led to difficulties utilizing this cognitive approach for students with learning and intellectual disabilities (6). Of the quantity of research on SRSD, only five experimental or quasi-experimental designs met the criteria for being acceptable research, while only nine single-subject designs were deemed of quality (24). None of the researchers who conducted studies on cognitive strategies addressed generalization of these skills to standards-based state assessments in writing.

Through reviewing the research on both cognitive and behavioral approaches, it can be determined that a behavioral approach for instruction in the use of strategies that provide explicit, teacher-directed instruction for all levels of the writing process is an essential component in teaching students with learning and intellectual disabilities to learn to write and generalize these skills to a proficient level on state assessments (7, 25). Although there are no other studies specifically addressing Fading Prompts through Graphic Organizers method (FPGO), due to the author creating the program, there is substantial research on other behavioral approaches that utilize graphic organizers. Researchers have found significant gains in writing for students with learning and intellectual disabilities as measured by Correct Word Sequencing (CWS), and the standardized TOWL-3, and maintenance of these skills through the use of the behavioral approach(16–18).

Due to NCLB there is a need for researchers to further address generalization of learned skills to state assessments. Researchers found that through the behavioral approach of fading prompts in graphic organizers, three students with learning disabilities were able to advance from below basic (1) to a level of proficient (3) on the PSSA, while two did not pass the assessment; they did advanced from a score of below basic (1) to basic (2) (26). Researchers found that all the common characteristics of students with learning and intellectual disabilities needed to be addressed in order to assist them in passing state assessments (27–29). Researchers have also found that when explicit instruction, such as utilized in a behavioral approach, is provided to students with learning disabilities they can perform at the same level as their nondisabled peers, maintain these skills over time, and generalize these skills to state assessments (30). The purpose of this quantitative study was to examine the performance scores on the PSSA writing prompts assessment following FPGO as a treatment for students with learning and intellectual disabilities by comparing archived pretest, posttest, and actual PSSA results to determine if significant differences existed. The participants’ PSSA results were also compared to the average state PSSA results for the IEP subgroup. As more is learned about the effectiveness of FPGO, schools may use this information to assist students in passing state assessments in the area of writing.

Proficiency on state assessments, such as the PSSA, is a concern for administration, teachers, parents, and students. If AYP is not met funding is reduced and government involvement is instilled within the school districts at varying levels depending on the number of consecutive years the goal is not met (2). Members of the IEP subgroup who have a disability in the area being measured are clearly at a higher risk for not performing at a level of proficiency (8). The issue of passing statewide assessments, such as the PSSA, is becoming even more important since some states already do not permit students who do not pass the test to receive a diploma (9).

Although there has historically been a controversy between advocates for cognitive and behavioral approaches to teaching, NCLB has caused it to be even more pressing. Due to NCLB, teachers need to find the most effective strategy for assisting students with disabilities in passing state assessments. Directly teaching the skills through behavioral techniques has been deemed successful for students with learning and intellectual disabilities due to their common areas of deficits (10–18). Although the research has shown behavioral approaches’ successfulness for students with learning and intellectual disabilities, the advocates for cognitive approaches continue to criticize behavioral approaches for being too rigid (11, 19).

A substantial amount of research on teaching writing over the last several decades has been based on cognitive approaches, such as product, process, and Self-Regulated Strategies Development (SRSD). A large portion of this research was conducted by Graham (20) or replicated his work. Early on Graham (20) has found difficulties in implementing cognitive strategies for students with learning and intellectual disabilities, which included deficits in composition, mechanics, and motivation (20–23). A review of the 30 years of SRSD research allowed researchers to find differences in strategies behavior, writing skills, knowledge, and motivation that led to difficulties utilizing this cognitive approach for students with learning and intellectual disabilities (6). Of the quantity of research on SRSD, only five experimental or quasi-experimental designs met the criteria for being acceptable research, while only nine single-subject designs were deemed of quality (24). None of the researchers who conducted studies on cognitive strategies addressed generalization of these skills to standards-based state assessments in writing.

Through reviewing the research on both cognitive and behavioral approaches, it can be determined that a behavioral approach for instruction in the use of strategies that provide explicit, teacher-directed instruction for all levels of the writing process is an essential component in teaching students with learning and intellectual disabilities to learn to write and generalize these skills to a proficient level on state assessments (7, 25). Although there are no other studies specifically addressing Fading Prompts through Graphic Organizers method (FPGO), due to the author creating the program, there is substantial research on other behavioral approaches that utilize graphic organizers. Researchers have found significant gains in writing for students with learning and intellectual disabilities as measured by Correct Word Sequencing (CWS), and the standardized TOWL-3, and maintenance of these skills through the use of the behavioral approach(16–18).

Due to NCLB there is a need for researchers to further address generalization of learned skills to state assessments. Researchers found that through the behavioral approach of fading prompts in graphic organizers, three students with learning disabilities were able to advance from below basic (1) to a level of proficient (3) on the PSSA, while two did not pass the assessment; they did advanced from a score of below basic (1) to basic (2) (26). Researchers found that all the common characteristics of students with learning and intellectual disabilities needed to be addressed in order to assist them in passing state assessments (27–29). Researchers have also found that when explicit instruction, such as utilized in a behavioral approach, is provided to students with learning disabilities they can perform at the same level as their nondisabled peers, maintain these skills over time, and generalize these skills to state assessments (30). The purpose of this quantitative study was to examine the performance scores on the PSSA writing prompts assessment following FPGO as a treatment for students with learning and intellectual disabilities by comparing archived pretest, posttest, and actual PSSA results to determine if significant differences existed. The participants’ PSSA results were also compared to the average state PSSA results for the IEP subgroup. As more is learned about the effectiveness of FPGO, schools may use this information to assist students in passing state assessments in the area of writing.

Materials and Method

The sample population was taken from a small town located in

northwestern Pennsylvania. The sample size included a total of 45

students, ranging in age from 13 to 18 years old, who were placed in the

learning support English setting by the IEP team in 8th or 11th

grade (PSSA testing grade levels) for the 2005-2010 school years. The

sampling included all students labeled with a learning disability in

writing or an intellectual disability who were exposed to FPGO

treatment, which was an inclusive group. In 2005-2006, the sample

included 7 students in the 8th grade. During 2006-2007, 7 students in the 11th grade were included. In 2007-2008, three 8th grade students were included and 11 students in 11th grade participated. In the 2008-2009 school year 7 students in the 11th grade were included. During the 2009-2010 school year 10 students in the 11th

grade were involved. The demographic characteristics of the 45 students

consisted of 34 students with a learning disability, which represents

76%, and eleven with an intellectual disability, which represents 24%.

Thirteen of the students were female, while 32 were male. Racially, 100%

of students were Caucasian, due to 99% of the population within the

school district being Caucasian.

The researcher utilized prompts selected from the PSSA writing assessment preparation book and the PSSA scoring rubric, as well as the results of the archived pretests, posttests, and the results of the actual PSSA for the 2005-2010 school years. The pretest and posttest results were determined through the use of the PSSA rubric as a measurement instrument to determine if students’ writing was at a score of 1- 4. The scale indicated below basic (1), basic (2), proficient (3), or advanced (4), as adopted in 1999 by the members of the Pennsylvania Department of Education. (31) A score of proficient or advanced is considered a passing score. Reliability for the PSSA was addressed through a stratified coefficient alpha, standard errors of measure (SEM), conditional standard errors of measure (CSEM) with the Rasch, decision consistency, and rater agreement. In regards to validity, the PSSA addressed the following: (a) test content, (b) response processes, (c) internal structure (d) the relationship between test scores and other variables, (e) the consequences of testing. (31)

Prior to the implementation of the FPGO as a treatment, students were presented with a PSSA writing prompt that was taken from a PSSA preparation book, which included narrative, informative, and persuasive prompts. Each student’s response was evaluated through the use of the rubric that was utilized within FPGO in order to provide specific feedback to students. The PSSA rubric was then utilized to derive a score of below basic (1), basic (2), proficient (3), or advanced (4). The scores were then reported as students’ baseline data due to the need to have the pretest and posttest scores reflect the same assessment tool, as the PSSA.

The teacher then utilized FPGO as classroom instruction. FPGO provided a graphic organizer that contained twenty-five boxes representing five paragraphs with at least five sentences in each. The method results in completing a writing response that consists of an introductory paragraph, three paragraphs as the body, and a closing paragraph. Students were provided with the FPGO step 1, which contains the most explicit set of prompts. As students became familiar with the process, prompts were slowly removed and the students were presented with FPGO step 2, which removes the names of the paragraphs, the prompting for the introductory sentence, and names of the topic and supporting sentences. When students reached a level of mastery, they were given FPGO step 3, which faded the prompting by removing all prompting through words, and left only numbers and letters. As skills continued to develop, students were presented with FPGO step 4, which provided them only empty boxes.

Once mastery of the skills had been met, students were provided with three pieces of blank typing paper and were expected to develop the graphic organizer independently by drawing the boxes. Having the students create their own graphic organizers was essential due to PSSA administration guidelines not allowing students any supplemental aids other than blank paper. Students progressed through the fading prompts steps at different speeds, but all students were expected to reach a level of proficiency.

One writing prompt was completed weekly to ensure retention. After exposure to FPGO and prior to the PSSA assessment, samples of the students’ written responses were evaluated by the researcher and three other trained teachers with the PSSA rubric. The teachers consistently derived the same scores. These data were reported as posttest data. A quantitative design was used to test if significant differences occurred between performance scores on the PSSA writing assessment following FPGO for students with learning and intellectual disabilities. The archived data used in this study was the result of a manipulation of the independent variable by presenting the extra stimulus of graphic organizers.

Four dichotomies for percent differences were utilized to determine if significant differences occurred in PSSA results after the implementation of FPGO. The first dichotomy compared the teacher administered pretests to the teacher administered posttests for the 2005-2010 school years. The second dichotomy compared the teacher administered pretests to the actual PSSA results to determine if differences existed. Rater reliability and generalization of the learned skills by the students were then addressed through a dichotomy of percent differences that compared the teacher administered posttests to the actual PSSA results. The fourth dichotomy compared the PSSA state administered local results for the students that received FPGO to the average PSSA pass and non-pass rates for the entire state of Pennsylvania’s IEP subgroups. Rater reliability was addressed through having the researcher re-score pretest and posttest data at a later time, having three other teachers also score the data, and comparing the archived posttest scores to the actual PSSA scores. As indicated, the PSSA rubric addresses reliability through a stratified coefficient alpha, standard errors of measure (SEM), conditional standard errors of measure (CSEM) with the Rasch, decision consistency, and rater agreement and validity through (a) test content, (b) response processes, (c) internal structure (d) the relationship between test scores and other variables, (e) the consequences of testing. (31).

The researcher utilized prompts selected from the PSSA writing assessment preparation book and the PSSA scoring rubric, as well as the results of the archived pretests, posttests, and the results of the actual PSSA for the 2005-2010 school years. The pretest and posttest results were determined through the use of the PSSA rubric as a measurement instrument to determine if students’ writing was at a score of 1- 4. The scale indicated below basic (1), basic (2), proficient (3), or advanced (4), as adopted in 1999 by the members of the Pennsylvania Department of Education. (31) A score of proficient or advanced is considered a passing score. Reliability for the PSSA was addressed through a stratified coefficient alpha, standard errors of measure (SEM), conditional standard errors of measure (CSEM) with the Rasch, decision consistency, and rater agreement. In regards to validity, the PSSA addressed the following: (a) test content, (b) response processes, (c) internal structure (d) the relationship between test scores and other variables, (e) the consequences of testing. (31)

Prior to the implementation of the FPGO as a treatment, students were presented with a PSSA writing prompt that was taken from a PSSA preparation book, which included narrative, informative, and persuasive prompts. Each student’s response was evaluated through the use of the rubric that was utilized within FPGO in order to provide specific feedback to students. The PSSA rubric was then utilized to derive a score of below basic (1), basic (2), proficient (3), or advanced (4). The scores were then reported as students’ baseline data due to the need to have the pretest and posttest scores reflect the same assessment tool, as the PSSA.

The teacher then utilized FPGO as classroom instruction. FPGO provided a graphic organizer that contained twenty-five boxes representing five paragraphs with at least five sentences in each. The method results in completing a writing response that consists of an introductory paragraph, three paragraphs as the body, and a closing paragraph. Students were provided with the FPGO step 1, which contains the most explicit set of prompts. As students became familiar with the process, prompts were slowly removed and the students were presented with FPGO step 2, which removes the names of the paragraphs, the prompting for the introductory sentence, and names of the topic and supporting sentences. When students reached a level of mastery, they were given FPGO step 3, which faded the prompting by removing all prompting through words, and left only numbers and letters. As skills continued to develop, students were presented with FPGO step 4, which provided them only empty boxes.

Once mastery of the skills had been met, students were provided with three pieces of blank typing paper and were expected to develop the graphic organizer independently by drawing the boxes. Having the students create their own graphic organizers was essential due to PSSA administration guidelines not allowing students any supplemental aids other than blank paper. Students progressed through the fading prompts steps at different speeds, but all students were expected to reach a level of proficiency.

One writing prompt was completed weekly to ensure retention. After exposure to FPGO and prior to the PSSA assessment, samples of the students’ written responses were evaluated by the researcher and three other trained teachers with the PSSA rubric. The teachers consistently derived the same scores. These data were reported as posttest data. A quantitative design was used to test if significant differences occurred between performance scores on the PSSA writing assessment following FPGO for students with learning and intellectual disabilities. The archived data used in this study was the result of a manipulation of the independent variable by presenting the extra stimulus of graphic organizers.

Four dichotomies for percent differences were utilized to determine if significant differences occurred in PSSA results after the implementation of FPGO. The first dichotomy compared the teacher administered pretests to the teacher administered posttests for the 2005-2010 school years. The second dichotomy compared the teacher administered pretests to the actual PSSA results to determine if differences existed. Rater reliability and generalization of the learned skills by the students were then addressed through a dichotomy of percent differences that compared the teacher administered posttests to the actual PSSA results. The fourth dichotomy compared the PSSA state administered local results for the students that received FPGO to the average PSSA pass and non-pass rates for the entire state of Pennsylvania’s IEP subgroups. Rater reliability was addressed through having the researcher re-score pretest and posttest data at a later time, having three other teachers also score the data, and comparing the archived posttest scores to the actual PSSA scores. As indicated, the PSSA rubric addresses reliability through a stratified coefficient alpha, standard errors of measure (SEM), conditional standard errors of measure (CSEM) with the Rasch, decision consistency, and rater agreement and validity through (a) test content, (b) response processes, (c) internal structure (d) the relationship between test scores and other variables, (e) the consequences of testing. (31).

Results

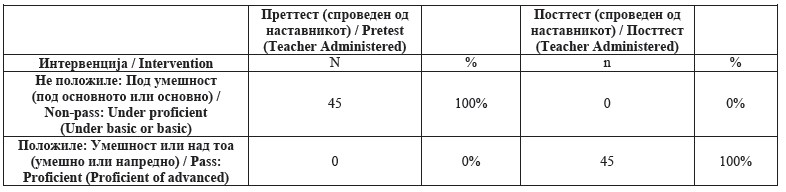

All 45 students received a below basic (1) on their archived pretest and

a proficient (3) score on their archived posttest. Forty-three students

earned a score of proficient (3) on the actual, archived PSSA

assessment; while two students received a score of basic (2) (see Table

1, for archived pretest, posttest, and PSSA scores). As indicated

earlier, the reliability and the validity of the actual PSSA assessment

were determined by the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

Table 1.Pretest, Posttest and PSSA results

Four dichotomies for percent differences were carried out. The results were calculated by subtracting the difference in percent between the two columns in either row. The outcomes of the first dichotomy for percent differences, which compared the percent of pass and non-pass rates when comparing the teacher administered pretests and posttests for the students with learning and intellectual disabilities that received FPGO for the 2005-2010 school years, resulted in FPGO making a 100% difference (100% - 0%=100%) in passing the PSSA, or not passing the PSSA (see Table 2, for dichotomy for percent differences for the pretest and posttest data).

Table 2.Dichotomy for percent differences in pretest and posttest data

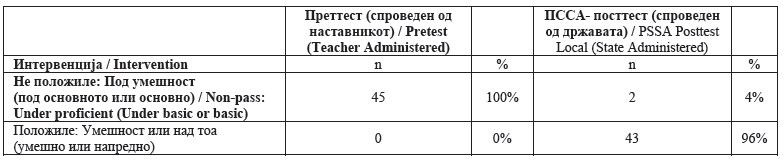

Therefore, it was determined that FPGO was effective in assisting the students with learning and intellectual disabilities in passing the standards-based state assessment of the PSSA at a significance level of 0.001, or 99.99% confidence level. The second dichotomy, which compared the percent of pass and non-pass rates through comparing the teacher administered pretests to the actual state administered PSSA, analysis showed that FPGO made a 96% difference (100% - 4% = 96% and 96% - 0% = 96%) in passing the PSSA, or not (see Table 3, for dichotomy for percent differences for pretest and PSSA data).

|

Table 3.Dichotomy for percent differences for pretests and PSSA data |

||

| ||

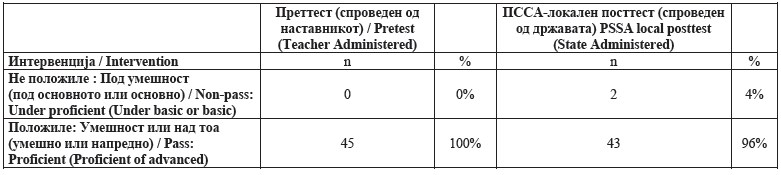

The third dichotomy, percent differences analysis, addressed the teacher administered posttests and compared them to the actual state administered PSSA results. The results found a 4% difference (4% - 0%=4% and 100% - 96%=4%), which indicated rater reliability and generalization of the learned skills by the students to the actual PSSA (see Table 4, for the dichotomy for percent differences for posttest and PSSA data).

Table 4.Dichotomy for percent differences for posttest and PSSA data

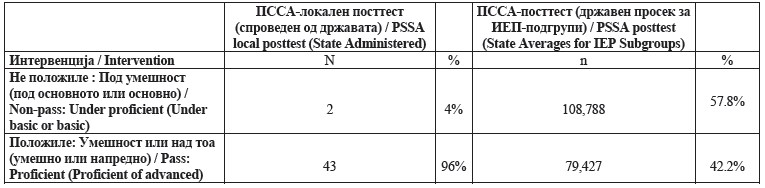

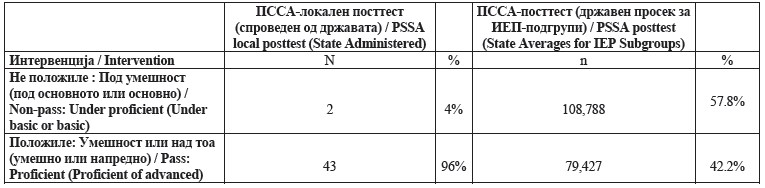

The fourth dichotomy compared the PSSA posttest state administered local results for the students that received FPGO to the average PSSA pass and non-pass rates of the entire state of Pennsylvania. The fourth dichotomy resulted in FPGO making a 53.8% (57.8% - 4%=53.8% and 96% - 42.2%=53.8%) difference for students with IEPs, which indicates learning and intellecttual disabilities, in passing the PSSA, or not (see Table 5, for dichotomy for percent differences for local and state PSSA data).

Table 5.Dichotomy for percent differences for the local and state PSSA data

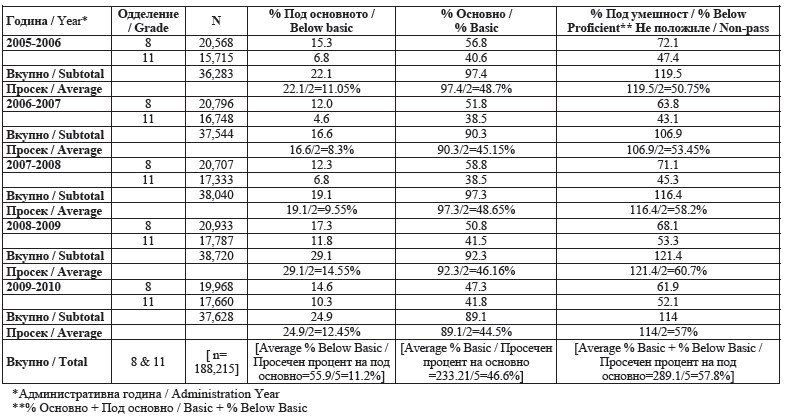

The PSSA data that were utilized to calculate the overall non-passing

percent for the entire state of Pennsylvania when addressing the IEP

subgroup was utilized in order to be the most reflective of the sample

addressed in this study. It is important to indicate that the state’s

IEP subgroup included all students with an IEP. Therefore, students that

did not have deficits in writing were included; while this study’s

sample addresses only students with an IEP reflecting deficits in

written expression. Of the 188.212 students with an IEP in the state of

Pennsylvania, 57.8% did not pass the PSSA (see Table 6, for PSSA data

utilized to calculate overall average non-passing percent).

Table 6. PSSA data utilized to calculate the overall average of non-passing percent

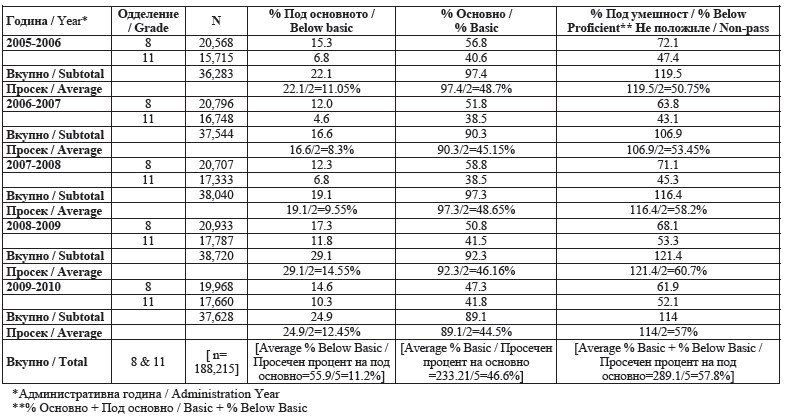

The PSSA data that were utilized to calculate the overall passing percent for the entire state of Pennsylvania when addressing the IEP subgroup, again reports all students with an IEP, not just students with disabilities in written expression. Although this included students who did not have deficits in writing, only 42.2% passed the PSSA (see Table 7, for PSSA data utilized to calculate overall average passing percent).

\Table 7. PSSA data utilized to calculate the overall average of passing percent

Based on the outcomes of the four dichotomies for percent, it was determined that significant differences in performance scores on the PSSA writing prompts assessment existed following FPGO treatment for students with learning and intellectual disabilities through comparing archived pretest, posttest, and actual PSSA results. It was further determined that the outcomes of FPGO generalized to the PSSA.

Discussion

Although the supporters of NCLB have placed a great deal of emphasis on performing at a level of proficient on state assessments, no studies address the effectiveness of cognitive approaches generalizing to state assessments, few studies have addressed the effectiveness of behavioral approaches generalizing to state assessments, such as the PSSA, and no other studies have addressed the use of FPGO. This research provides additional insight into the effectiveness of behavioral approaches to teaching writing, as well as addresses how effectively these skills generalize to state assessments, such as the PSSA. Only 2 of the 45 students in this study did not pass the PSSA. However, both students advanced from a score of below basic (1) to a score of basic (2). It is also important to indicate that the 2 students who did not pass were identified as having an intellectual disability. The current review of literature excluded these students.

The major limitations within this study focus around the sampling procedures and the research design. The sampling procedures were based on accessibility and convenience and did not include random sampling. True random sampling did not occur since the testing group was established based on students being identified with a learning or intellectual disability and placed in the learning support setting for their English instruction by the IEP team and parent consent. Convenience sampling led to including only students in one school district, which resulted in all of the students within the sample population being Caucasian. Given that the PSSA is only administered to middle and high school students in 8th and 11th grades, the results of the FPGO were not tested on any other grade levels of students.

The structure of the study resulted in only one teacher implementing FPGO treatment for teaching writing. Although this controlled for treatment fidelity, which refers to following the exact procedures specified by the researcher, this also leads to questioning whether another teacher would have the same success with FPGO. It would be beneficial to generalize the outcomes of this study to the entire state of Pennsylvania in order to increase school districts’ AYP to comply with NCLB; however, the lack of random sampling makes generalization difficult. Comparing the local state administered PSSA results to the entire state of Pennsylvania’s IEP subgroups’ non-pass and pass percent also led to comparing students with disabilities in writing at the local level to students that may not have a deficit in writing in the state’s IEP subgroup.

There were further limitations due to the research design. In the quasi-experimental research design, the researcher is attempting to identify cause and effect by controlling the independent variable. Although the research was collected over a span of several PSSA testing years, limitations of not having a control group or returning to baseline as a means of comparison make it difficult to insure that the independent variable was controlled. The research design did not allow for return to baseline due to the fact that the students would automatically utilize the learned writing skills that were developed during the treatment phase.

Further studies should address sampling limitations by conducting a larger scale study to include several school districts from other demographic areas. The inclusion of numerous school districts may also be needed to create a stratified sample to represent other ethnic groups. Additional studies should also address the effect of FPGO on students in 7th, 9th, and 10th grades.

Further studies should also be conducted to address any structural limitations within this study. Larger scaled studies should evaluate the effectiveness of FPGO treatment when different teachers with varying backgrounds implement the treatment. In order to further explore the amount of control that was exhibited over the independent variable of adding an extra stimulus of graphic organizers to the prompts, additional research should be conducted to reflect the use of a control group. The results of this program should be compared to other strategies for teaching writing, such as cognitive approaches that are currently being utilized.

Conclusion

Given that the only two students who did not pass the PSSA with a score of proficient (3) were identified as having intellectual disabilities, additional studies that compare students with learning disabilities versus students with intellectual disabilities may provide further insight into the effectiveness of the program. Additional research should also be conducted on the effectiveness of FPGO treatment with students who do not have disabilities. Based on the outcomes of this study, which indicate that FPGO treatment led to significant differences between performance scores on the PSSA writing assessment for students with learning and intellectual disabilities, it is highly recommended that this program be utilized at least for students with learning and intellectual disabilities until further research can be done.

Given that the only two students who did not pass the PSSA with a score of proficient (3) were identified as having intellectual disabilities, additional studies that compare students with learning disabilities versus students with intellectual disabilities may provide further insight into the effectiveness of the program. Additional research should also be conducted on the effectiveness of FPGO treatment with students who do not have disabilities. Based on the outcomes of this study, which indicate that FPGO treatment led to significant differences between performance scores on the PSSA writing assessment for students with learning and intellectual disabilities, it is highly recommended that this program be utilized at least for students with learning and intellectual disabilities until further research can be done.

Conflict of interests

Author declare that have no conflict of interests.

Author declare that have no conflict of interests.

References

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment