|

Recived: 20.01.2015

Accepted: 25.02.2015

Original

article

|

Abstract

|

|

|

|

International

Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF, WHO, 2001) is a

constructive framework for quality assessment and treatment in Logopedics

(Speech Language Therapy). The current research study makes an attempt to

introduce this standard into logopedical practice and applied research to

measure the quality of life of persons with fluency disorders, such as

stuttering. The quality of life is a modern multidimensional construct that covers health-medical, psychological, social and economic

factors. Good level of communication and stabilized

fluency is of key

importance to improve the quality of life of persons who stutter.

The purpose of the study was

to show a model of assessment, treatment and evaluation of the efficacy of

the non-avoidance approach in adult stuttering therapy.

|

|

Methods: CharlesVan Riper’s non-avoidance approach for an

intensive therapy. Participants were 15 adults who stutter with an

average age 25.2 years.

Results: Specific

significant decreasing of the two main parameters: index of dysfluencies

immediately after the intensive therapy as well as duration of disfluences in

seconds. The changes in speech fluency before and after the intensive therapy

as well as 3 years after this therapy were obtained regarding the duration of

disfluencies and index of dysfluency.

Conclusion: The

present model of an intensive non-avoidance therapy format for adults with stuttering disorders was

successfully applied for the Bulgarian conditions. Improved fluency is an

important factor for quality of life improvement of persons with stuttering

disorder.

|

|

|

|

Keywords: International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

(ICF); fluency disorders; stuttering; stuttering therapy; evidence-based practice;

quality of life; outcomes measures.

|

|

|

|

Introduction

|

|

|

|

Research status in the relevant topic in Bulgaria

According to WHO the understanding of the ICF model in respect to

stuttering as a type of fluency disorder requires interdisciplinary

interpretation and competence (1).

The application of the ICF is a constructive framework for quality

diagnostics and speech therapy of stuttering in many advanced countries in

the EU, the U.S. and Australia. It

is known that Yaruss and Quesal (2)

adapted the ICF for the needs of Logopedics (Speech-Language Pathology or

Therapy). They propose that the classification should be adopted as a framework

for reporting the speech therapy efficiency in relation to stuttering. The

ICF model describes how stuttering can be viewed according to the following

perspectives: (i) presumed

etiology, (ii) impairment in body function (observable stuttering behaviors),

(iii) personal factors and affective, behavior and cognitive reactions, (iv)

environmental factors, (v) activity limitations and participation restrictions.

Unfortunately, in Bulgaria

there are no research and science-based measurements of speech and language treatment services with the use of the ICF model. The National Scientific

Fund of Bulgaria (the

NSF) has funded only one highly successful research project in the professional

field of Public Health and Logopedics (2009-2012, contract number DTK 02/33).

It was about Evidence-Based Practice in Fluency and Voice Disorders, directed by D. Georgieva, South-West University “Neofit Rilski”. The

outcomes of intensive speech therapy with people of all ages who stutter were

published in peer reviewed international journals (3, 4, 5). Medical

treatment, health communication, social and psychological services for people

who stutter were applied to enhance the quality of life of clients from the

South-western region of Bulgaria, which include the capital, Sofia. A long

term goal of the study was to encourage the development of health tourism in the area, which is

defined as a region of health in a number of projects under the Sixth and

Seventh EU Framework Program.

The stuttering outcome is a

change in the client’s current and future fluency status that can be attributed

to antecedent health care (6). Outcomes refer to the effects of therapy,

programs or policies in individuals or population. Outcomes may also be

defined as changes in status attributed to a specific intervention or

therapy.

Within the proposed study

below, an attempt is made aiming to introduce this ICF standard practice in Logopedic and Logopedic applied research for measuring the multiple outcomes in individuals with stuttering.

|

|

|

|

Relevance of scientific problems in Bulgaria

and Europe

The EU Statistics Classification was accepted in Bulgaria in

2008. According to the EU Statistics Classification of 1999 and its

methodological handbook ISCED 97 Logopedics (Speech Language Therapy) is

considered a health profession and is located in professional direction 726

physiotherapy and rehabilitation. As a new member of the EU, Bulgaria

undoubtedly adheres to these rules. In July 2009, the Speech Language Therapy

program at South-West University in Blagoevgrad,

Bulgaria

successfully completed the official procedure of accreditation and evaluation

as part of the health sciences professions. This act created the required

conditions for conducting significant research in the field of Speech

Language Pathology following the ICF model.

Some

statistical data on communication, speech and language disorders in Bulgaria: 2.5% of the country’s total

population, or 150 000 people, are affected by stuttering or other

dysfluency type. 4% of school aged children suffer from stuttering (7). The

Bulgarian healthcare system offers no logopedic treatment for adolescents and

adults who stutter. In a number of international publications and world congresses,

the country is being criticized for not offering speech therapy service to

adult persons who stutter (8–11). The criticism, directed at the Bulgarian practice, enforced European

standards for the provision of quality speech therapy and development of

instruments for measuring the quality of life of persons with communication

disorders as a whole.

Bulgaria

participated successfully in a network project of 65 European universities,

funded by the European Social Fund entitled "Network for Tuning

Standards & Quality of Educational Program for Speech Language Therapists

in Europe" 2010–2013, Project number 177 075-LLp-1-2010-1-FR-EARSMUSENWA

(12) and was awarded a Fulbright research grant 2013 "Evidence-Based

Practice through Acoustic and Electroglottographic Characteristics Measuring

in Stuttering and Voice Disorders" - the only research project in the

field of speech therapy in Bulgaria won by the author of the present article

(13). In the frame of those projects the new paradigm “evidence-based

practice” in accordance with the ICF model was strongly recommended.

The new

concept for the application of the ICF classification in the field of

communication disorders (in the context of this current topic: stuttering) is

not known by Bulgarian speech language therapists. It is fundamental with

respect to speech language pathology science and therapy in some countries of

the European Union, the USA,

Australia and Canada. This

new paradigm refers to an approach in which the current, highly qualitative

research practiceс attempt to provide data not only about the clients' satisfaction

from the comprehensive speech service, but also about the clients' quality of

life. In Bulgaria,

in general, no systematic publications on the problem have been published,

even though in the European (CPLOL) and international (IALP) speech language

pathology organizations this model is specified as a standard.

The medical

model of stuttering seeks to reveal the causes and to provide proper therapy

for the persons with this communication disorder. Published scientific

studies in the U.S., Canada, Australia; England draw attention to the

diagnosis of the external, visible characteristics of stuttering and puts

minor emphasis on the evaluation of the experience of the person who stutters

as a speaker (14–17).

The social, psychological and logopedical model focuses on the inclusion of

the person who stutters in the society and also emphasizes the quality of

his/her life.

The review

of the Bulgarian literature indicated a lack of knowledge of the ICF model in

the country (see Table 1).

Table

1. Application of the International Classification of

Functioning, Disability, and Health - ICF, WHO, (1)

abroad and in Bulgaria,

comparative analyses regarding the stuttering disorder studies

|

|

ICF-компоненти /

The ICF components

|

САД, Австралија, Канада, Англија

/ The USA,

Australia, Canada, England

|

Бугарија /

Bulgaria

|

|

Нарушувања на телесната функција / Body function disorders

|

Conture (18); Johnson (19); Riley (20);Yairi and Ambrose (21)

|

Не / No

|

|

Нарушувања на телесната структура / Body structure disorders

|

Chang, Erickson,

Ambrose, Hasegawa-Johnson, & Ludlow

(22); Foundas, Bollich, Corey, Hurley, & Heilman (23)

|

Не / No

|

|

Индивидуално- контекстуални фактори / Individual

contextual factors

|

Cooper (24);

Manning (25); Shapiro (26); Sheehan (27); Van Riper (28); Watson (29)

|

Не / No

|

|

Контекстуални фактори на животната средина / Environment-based contextual

factors

|

Craig A, Hancock

K, Tran Y, & Craig M (30); Klein & Hood (31); Brutten & Shoemaker

(32); Ornstein & Manning (33); Woolf (34); Wright & Ayre (35); Ayre

& Wright (36) Yaruss

& Quesal (2); Yaruss (38)

|

Georgieva, (9), K. O. St. Louis, Filatova, Coskun,

Topbas, Ozdemir, Georgieva, McCaffrey,

George (37)

|

|

Ограничувања во активностите и рестрикции на

учество / Activity limitations and participation restrictions

|

Некои автори од САД и Австралија сметаат дека

квалитетот на животот е концепт поврзан со пелтечењето: Craig et al., (39);

Klompas & Ross (40) / Some authors from the USA and Australia consider

the quality of life as a concept, related to stuttering: Craig et al., (39);

Klompas & Ross (40).

|

K. O. St. Louis, Filatova, Coskun, Topbas, Ozdemir, Georgieva, McCaffrey,

George (41); Georgieva, Fibiger (3); Georgieva (4, 5).

|

Легенда: / Legend:

|

Медицински модел на

интерпретација на пелтечењето според МКФ / Medical model of stuttering interpretation according

to ICF

|

|

Логопедски и психолошки

модел на интерпретација на пелтечењето според МКФ / Logopedical and psychological model of stuttering

interpretation according to ICF

|

|

Логопедски и

социjален модел на интерпретациjа на пелтечењето според МКФ / Logopedical and

social model for stuttering interpretation according to ICF

|

|

This fact makes the scientists and

especially speech language therapists recognize the need for broad-based

implementation of evidence-based assessment and therapy for this complex

communication disorder.

The

purpose of the current study was to develop an ICF model of assessment,

therapy and evaluation of the efficacy of the applied treatment approach in

adult stuttering cases.

|

|

|

|

Present Study

Methodology

|

|

|

|

This research study was

built on the ICF model (1), which is a standard for speech therapists,

according to the IALP guidelines for initial education in Speech-Language

Pathology and the standards for practicing the clinical Logopedic profession

(42–44).

Methods

Charles Van Riper’s non-avoidance approach for an

intensive therapy (IT) format for

adults was applied (45). Full and detailed description of the study

procedures were published by Georgieva and Fibiger (3), Georgieva (4) and Georgieva (5).

|

|

|

|

Basic

considerations

The design of the therapy program was elaborated by Steen Fibiger and

was based on the following considerations:

ü Van Riper’s stuttering modification approach

was applied.

ü The team of speech therapists consider

motivation as a major element in the adult stuttering therapy (AST). A lack

of motivation was observed for one adult. The possible explanation was a

reflection of discouragement because of the ‘poor” results of the precedent

treatment.

ü WASSP Summary Profile was applied as a way of

measuring change in feelings, thoughts and behaviors and planning future management

(35, 36). This profile aims to record how the person who stutters perceives

his or her stuttering at the beginning and the end of a block of speech and

language therapy. WASSP

is an indicator for improvement in the quality of life after the therapy

period.

ü The AST requires involvement of four speech language therapists.

ü The official training language was Bulgarian, but all of the

participants were fluent in English.

Specific therapy methods for assessment (SSI-3)

and treatment of stuttering in adults, as well as measurement of the

effectiveness of Logopedic interventions (46) were also conducted.

The

application of voice acoustic analysis of the voice of adults who stutter has

also been planned using computerized speech laboratory (CSL) and specific

softwares as RTP (Real Time Pitch), and EGG

(electroglottography), (47, 48). To take these measures in voice disorders

is not obligatory but advisable.

It is intended

to use these various tools in the field of Public Health - Logopedics to

achieve fluent speech (for a detailed

description see Table 2 below).

|

|

Table 2. ICF components, providing a detailed stuttering description in the current research

|

|

|

|

Преглед на МКФ-компоненти во проектот / ICF components for project examination

|

Препорачани специфични дијагностички алатки за евалуација на

ефективноста од логопедската терапија според Yaruss, (49, 50) / Recommended specific

diagnostic tools for evaluating the effectiveness of the speech intervention on Yaruss, (49, 50)

|

|

Оценка и дијагностика на нарушувањето на флуентноста / Fluency disorder assessment and diagnosis

|

Инструмент за

евалуација на степенот на тежина на пелтечењето, чиј автор е Riley, (46) / Stuttering

Severity Instrument SSI-3,

authored by Riley, (46)

|

|

Оценка на реакциите на пелтечењето / Assessment

of stuttering reactions

|

1.

S-24

Andrews & Cutler (51

2.

Скала за пресметување на самоувереноста на

возрасни кои пелтечат при пристапување и одржување на флуентноста во различни

говорни ситуации (Ornstein

& Manning, 52) / Self-Efficacy

Scale for Adults Who Stutter (Ornstein & Manning, 52)

|

|

Истражување на

самооценката на лица кои пелтечат / Research on the stutterer's self-assessment

|

Профил за самооценка при пелтечење Write & Ayer (35, 36) /

Write & Ayer Stuttering Self Rating Profile

(

35,36)

Протоколи на Crove (53) / Crowe’s

Protocols (53)

|

|

Детална оценка на

говорното искуство на лицето кое пелтечи - мерење на квалитетот на животот / Comprehensive diagnosis of the speech experience of

the person who stutters - measuring the quality of life

|

Севкупна оценка на

искуството кое лицето го има од своето пелтечење - Yaruss and Quesal, (2, 54) – во процес на превод и адаптација за бугарски

услови / Overall

Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering -Yaruss and Quesal, (2, 54) – in process of translation and

adaptation for Bulgarian conditions

|

Specific research activities

The main goal of

the present study was to assess therapy outcomes using a variety of stuttering

measurements based on Van Riper’s intensive therapy

approach. Second research was conducted to specify any changes that are adopted in different

speech situations (in the stabilization phase), and to demonstrate that changes

are maintained after the therapy (1, 2, and 3 years after the treatment).

Measurement

for adults includes determination of index

of dysfluencies (ID) - the number of stuttering events divided by the

number of syllables, and duration of

dysfluences (DDs) - in seconds, for the three longest stuttering events.

Specific

stuttering measurements:

Application of SSI - 3 developed by Riley (46) – (Table

2 and

Table 3).

|

Table 3. Stuttering

Severity Instrument for Adults – results after the assessment before the

intensive treatment

|

|

|

|

|

Клиент / Client

|

Пол / Gender

|

Почетен SSI-резултат

(процент) / Initial

SSI score (percentage)

|

Почетен степен на тежина / Initial severity

|

|

S1

|

Ж / F

|

27 (60%)

|

Умерен / Moderate

|

|

S2

|

М / M

|

25 (41%)

|

Умерен / Moderate

|

|

S3

|

М / M

|

37 (96%)

|

Многу тежок /

Very severe

|

|

S4

|

М / M

|

46 (99%)

|

Многу тежок

/ Very

severe

|

|

S5

|

М / M

|

46 (99%)

|

Многу тежок

/ Very

severe

|

|

S6

|

Ж / F

|

27 (60%)

|

Умерен / Moderate

|

|

S7

|

М / M

|

25 (41%)

|

Умерен / Moderate

|

|

S8

|

М / M

|

46 (99%)

|

Многу тежок

/ Very

severe

|

|

S9

|

М / M

|

34 (88%)

|

Тежок / Severe

|

|

S10

|

М / M

|

35 (89%)

|

Тежок / Severe

|

|

S11

|

Ж / F

|

28 (61%)

|

Умерен / Moderate

|

|

S12

|

М / M

|

31 (77%)

|

Умерен / Moderate

|

|

S13

|

М / M

|

46 (99%)

|

Многу тежок

/ Very

severe

|

|

S14

|

М / M

|

35 (89%)

|

Тежок / Severe

|

|

S15

|

М / M

|

34 (88%)

|

Тежок / Severe

|

Легенда

/ Caption: Ж(женски); М (машки); SSI = степен на тежина за пелтечењето / F = female; M = male;

SSI = Stuttering severity instrument

|

Participants: Fifteen adults who stutter participated (average age

was 25.2 years). All of them had

experienced fluency shaping therapy prior to the current intensive stuttering

modification therapy (averaging 12.6 years prior to the present study; range

= 4–23 years). One participant had stuttering modification therapy (one year

prior to participation in the intensive course).

Inclusion criteria: To participate, adults who stutter had to (i) be older than 20

years; (ii) have taken part in a previous treatment trial, and (iii) have

exhibited a range of stuttering severities that ensured the sample was

representative.

Data collection: Each client’s files were

reviewed (assessment reports and

progress reports). Three types of files were recorded during the initial assessment,

at the onset of IT, and the end of the five day intensive therapy, 1, 2, and

3 years after the IT.

Measurements: (i) Changes in speech fluency the 1st, 2nd and 3rd year after the intensive treatment with adult stutterers. Evaluation

of stuttering severity was based on stuttering frequency during oral reading

and spontaneous speaking. The data collection mentioned above consists of two

fluency and affective-based measurements, which were assessed before

intensive treatment and immediately after the intensive treatment, as well as

1, 2, and 3 years after the IT.

Precision of measures refers to

the exactness with which stuttering dysfluencies can be measured.

|

|

|

Reliability of measures: After the IT and each of the

stabilization phase sessions, a five-minute video-recorded spontaneous speech

sample was obtained from each of the participants. Each speaking sample

contains at least 300-400 syllables to ensure reliable results. External independent

evaluation was provided by an independent clinician. He reported “measurement

agreement” 95%.

Validity: predictive validity

(criterion validity) is a gold standard because it refers to the ability to

predict future measures. At the end of the intensive adult stutterers'

therapy we could accurately predict whether clients would maintain their

gains.

Evidence-based practice: A good clinical practice should and must be

based on evidence. The clients’WASSP profiles were analysed individually.

The study offers a quantitative measure not necessarily requiring

normative comparisons regarding 2011

and 2012 – the so-called post treatment

period.

Statistics methods: The data obtained were

calculated using the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test for hypotheses testing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Results and discussion

|

|

|

|

|

|

Changes in

speech fluency

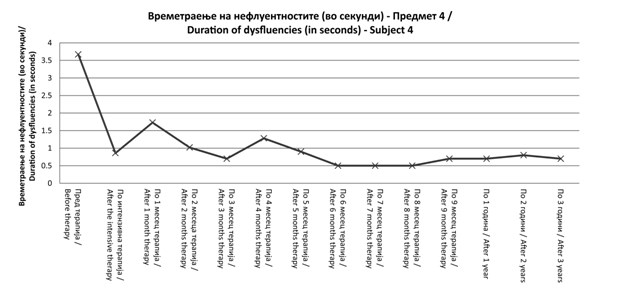

Figure 1. Duration of

dysfluencies in seconds at the beginning versus end of the intensive treatment,

and one, two and three years after the intensive treatment for subject 4

|

At the beginning of the treatment

DD was 3.8 seconds and immediately

after IT this parameter reduced to 0.8 sec. Some changes in DD were observed over the first and second months

after the IT. For this client it was

difficult to maintain some of the new speech modification techniques like

pull-out and cancellation. The preparatory set technique was applied successfully

and stabilized by the client after 6 months of training after the IT. The

0.5sec DD increased slightly 3 years

after the IT.

Embarrassment, fears and anger

were typically presented after the student exam session. They characterized the so-called educational disadvantages of

client 4 and they are related to his poor educational achievements in that

period.

|

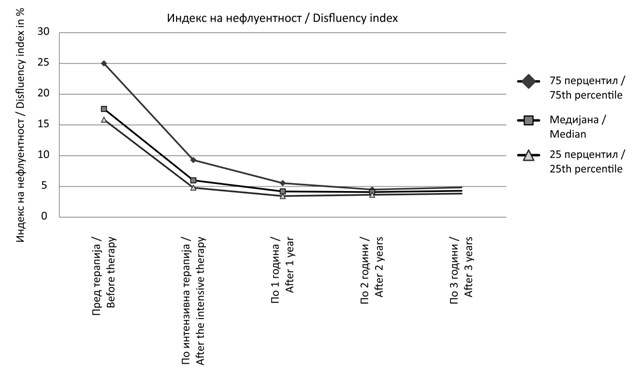

Figure 2. Duration of

dysfluencies in seconds at the beginning versus end of the intensive treatment,

and one, two and three years after the intensive treatment for all participants

(n=15), (5, 13)

The Wilcoxon signed ranks

test confirmed that there was a

reduction of DDs before and after intensive treatment (Z – 3.

408; p < 0.001):

§

Before IT and 1 year after IT (Z – 3. 408; p

< 0.001)

§

Before IT and

2 years after IT (Z – 3. 409; p < 0.001)

§

Before IT and

3 years after IT (Z – 3. 408; p < 0.001).

Sustained reduction in DDs was achieved (p < 0.001). There was

a significant reduction in the average duration of fluency disruptions.

There was a statistically significant

reduction of DDs:

§ After IT and 1 year after IT: (Z – 0.692; p < 0.489)

§ After IT and 2 years after IT: (Z – 0.684; p < 0.494)

After IT and 3 years after IT: (Z

– 1.329; p < 0.184).

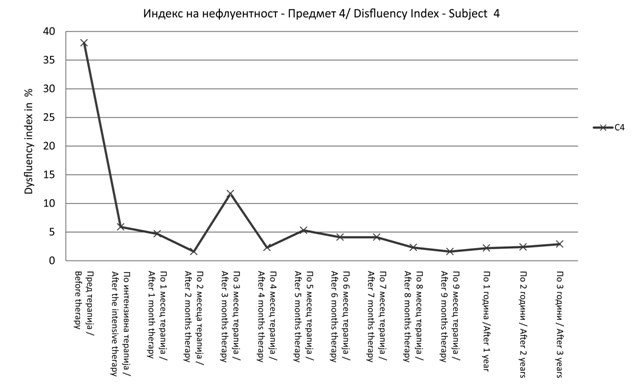

Figure 3. Dysfluency

index in % at the beginning versus end of the intensive treatment, and one,

two and three years after the intensive treatment for subject 4

Marked

decreases from 38% DI before

the IT to 6% after the treatment course. Two months after the IT in the stabilization phase the client manifested

low level of different types of disfluences with – only 0.3% variation in DI.

This means that he manifested fluent speech. There was a period of instability and variation of the DI curve where

the participant reverted to dysfluent speech (movements between 0.3% and a rapid increasing to 11.5%). From the client's files it was possible to show that he reported strong frustration

between the 2nd and 4th months after the IT, related to associated health problems. Subsequently,

the curve demonstrated strong maintenance of the fluent speech behavior and

stabilization of fluency 3 years after the IT. To summarize, the client needed a prolonged period of time to consolidate the

newly established speech behavior when the totally new speech techniques were

applied in this sensitive period. The overall pattern showed that in order to

stabilize the new stuttering behaviors acquired during the IT, continued

treatment and psychological and social support for a long period are needed.

Such long term support allows stabilization to continue and helps manage

relapses to the old stuttering behaviors.

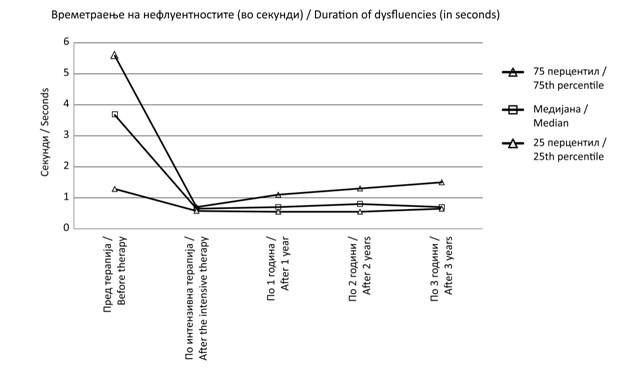

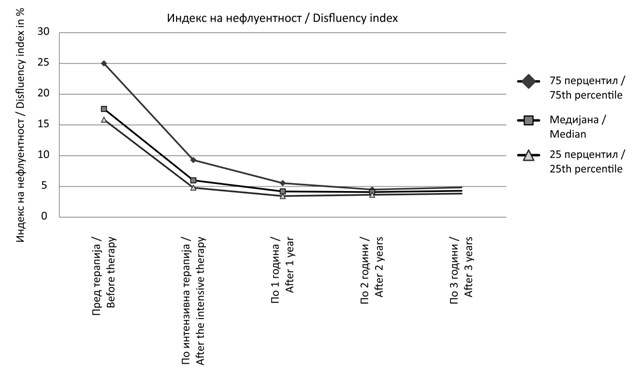

Figure 4. Dysfluency Index at the beginning versus end of the intensive therapy and one, two and three years after the intensive therapy for all

participants (n=15), (5, 13)

|

Significant changes regarding reduction of disfluency index were found

before and after intensive therapy (Z – 3.408; p < 0.001). DI before and after the IT show the next results:

§

Before

and after the 1st year (Z – 3.411; p < 0.001)

§

Before and after the

2nd year (Z – 3.408; p < 0.001)

§

Before

and after the 3rd year month (Z – 3.408; р < 0.001).

DI after the IT and

after 1, 2, 3 years post therapy show:

§ After

IT and after the 1st year (Z – 3.068; p < 0.002)

§

After IT and after

the 2nd year (Z – 3.408; p < 0.001)

§ After IT and after the 3rd year

month (Z – 3.202; р < 0.001).

|

|

|

|

WASSP Individual case results

Subject 4’s individual results and their

discussions are presented in this section. The initial SSI – 3 score was 46 (99%) which reflects very severe stuttering. The WASSP profile is shown in Figure 5.

The

WASSP profiles strongly support the observation of changes in the individual

stuttering behaviors before and after the IT as well as affective, emotional,

cognitive and social changes. In the individual case of client 4 (with very

severe initial stuttering) remarkable speech dysfluency changes were observed

immediately after the IT concerning all eight of the parameters examined.

Only one of the examinees’ WASSP profile parameters did not change after the

intensive course (negative thoughts during

speaking). This could be explained by the client’s inability to admit how

severe his stuttering was, as well as feelings and avoidance at the beginning

of the course. The changes were also impressive concerning Avoidance. The

present Van Riper’s non-avoidance approach requires

changes in the typical avoidance behavior through desensitization in

different speech situations. For the experienced clinician it is easy to observe decrease

of the avoidance attitude in all 4 areas: of words (from 6 to 3); of

situations (from 4 to 1); talking about stuttering with others (from 5 to 1),

and admitting problems to yourself (from 7 to 1). To conclude, client 4

reported a change of progress and reduction of scores for all five subscales

in WASSP.

|

WASSP-рејтинг

/ WASSP rating

sheet

|

|

Никој

/ None

|

Мн. тешко

/

Very

severе

|

|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

|

Однесувања

при пелтечење /

Stuttering behaviors

|

Фреквенција на пелтечење /

Frequency of stutters

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Физичко водење борба при пелтечење / Physical struggle

during stutters

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Траење на пелтечењата /

Duration of stutters

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Неконтролирано пелтечење / Uncontrollable stutters

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Итност/стапка на брз говор /

Urgency/fast speech

rate

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Поврзани фацијални/телесни движења / Associated facial/body

movements

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Општо ниво на физичка тензија /

General level of

physical tension

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Губење на контактот со очи /

Loss of eye contact

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Друго / Other

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Мисли

/ Thoughts

|

Негативни мисли пред зборување / Negative thoughts

before speaking

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Негативни мисли во текот на зборувањето / Negative

thoughts during speaking

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Негативни мисли по зборувањето / Negative thoughts

after speaking

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Чувства

/ Feelings

|

Фрустрација / Frustration

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Срам / Embarrassment

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Страв / Fear

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Лутина / Anger

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Беспомошност / Helplessness

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Друго / Other

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Избегнување

/ Avoidance

|

Брз зборови / Of words

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Вон ситуација / Of situations

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Не се зборува со други за пелтечењето /

Of talking about

stuttering with others

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Непризнавање на проблемот на себеси /

Of admitting your

problem to yourself

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Недостаток

/ Disadvantage

|

Дома / At home

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Друштевн / Socially

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Едукациски / Educationally

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

На работа / At work

|

1

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Забелешка: во третата колона: 1 - првата WASSP-евалуација; 2 = втората WASSP-евалуација (по интензивниот третман) /

Note:

in the 3rd column: 1= the first WASSP evaluation; 2=second WASSP

evaluation (after the intensive treatment)

|

Figure 5. Wright

& Ayer Stuttering Self-rating Profile (WASSP) summary of the client 4

|

|

|

|

His

explanatory comments in the last section of his profile revealed that he

had developed realistic expectations about stuttering outcomes. For

client 4, the fluency shaping approach had little or no lasting effect

which contrasted with the results of the non-avoidance approach in the

present study. The non-avoidance stuttering modification approach is

primarily a phenolmenological treatment, which is difficult to evaluate

in quantitative terms.

|

|

|

|

WASSP Group results

The set of WASSP subscales

results revealed considerable positive changes in response to participation

in the therapy course for the

majority of the participants. It includes behaviors, thoughts, feelings,

avoidance and disadvantage scales. They reported a visible change of

progress in all five subscales of the WASSP. The majority of clients were strongly motivated and reduced their degree of

stuttering from the

beginning of the intensive therapy. The rest of the WASSP

parameters changed in positive way.

|

|

|

|

Conclusion

|

|

|

|

The positive changes in speech

fluency before and after the intensive therapy and in the follow up period

(one, two and three years after the intensive therapy) were obtained

regarding the two essential parameters: (i) duration of dysfluencies, and

(ii) index of dysfluency (5, 13).

Improvement in stuttering

duration was observed immediately upon completing the intensive therapy. This

was reflected in a statistically significant reduction in the number of

stuttered utterances per minute. In the period of nine months stabilization

phase, one year, two years and three years after the therapy these positive

changes were maintained.

Although therapy was for a

limited time, this stuttering non-avoidance

approach intensive therapy provided the clients with new key experiences and

feelings that allowed them to progress based on their own effort.

Usually,

Bulgarian speech therapists prefer to apply fluency shaping approach and are

much more familiar with it. While the non-avoidance approach is a classic example of stuttering

modification approach to stuttering therapy, it is only one variant of many

stuttering modification therapies. We do not know whether these results can be

generalized to other stuttering modification approaches. Perhaps

simply participating in the present type of group stuttering intervention may

be sufficient to bring about the positive changes of the type and magnitude

that we observed

(5, 13).

Results from this study

showed that International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

are a beneficial framework for quality assessment and therapy in logopedics regarding stuttering. This study introduced for the first time in Bulgarian logopedical

practice stuttering modification approach and represents a good example of

therapy outcomes evidence-based measurement.

|

Acknowledgement

This study was funded in the frame of the South-West

University “N. Rilski”, Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria research project: Evidence-based

stuttering management and measurement: Outcomes for a Camperdown stuttering

treatment (2015).

Conflict of

interests

Author

declare that have no conflict of interests.

|

References

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. International Classification of

Functioning, Disability, & Health. Geneva:

World Health Organization. 2001.

2. Yaruss JS, Quesal RW. Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s

Experience of Stuttering (OASES): documenting multiple outcomes in stuttering

treatment. J Fluency Disord 2006; 31: 90-115.

3. Georgieva D, Fibiger S. Intensive Non-avoidance Group Therapy with Adults

Stuterers: Experience from Bulgaria.

Dansk Audiologopaedi (Denmark).

2010 Sept; 3: 24–30.

|

|

4. Georgieva

D. Intensive Non-Avoidance Group Therapy with Adults Stutterers: Preliminary

Results. Proceeding of the International Conference of Stuttering (Editor Giacomo Soncini), Prima

edizione, 7-9 June, Roma: Omega Edizioni; 2012; 163–171.

5. Georgieva D. Intensive

Non-Avoidance Group Therapy with Adults Stutterers: Follow up Data. Proceedings

from the 10th Oxford Dysfluency Conference, St. Catherine college,

Oxford, UK; 2015, July (in press).

6. Golper LA, Frattali CM.

Outcomes in Speech Language Pathology. Second edition. NY: Thieme, 2013.

|

|

7. Ivanov

V. Logopedics. Sofia:

Nauka i izkustvo, 1973 (in Bulgarian).

8. Georgieva

D, Goranova E. The treatment of fluency disorders: experience in Bulgaria. Presentation

at the 7th Oxford

Dysfluency Conference; 2005.

9. Georgieva

D. Speech situations, increasing the degree of

stuttering in persons aged 13–16 – PhD thesis, Sofia University, Bulgaria; 1996.

10. Fibiger

S, Peters H, Euler H, Neumann K. Health and human services for persons who

stutter and education of logopedists in East-European countries. J Fluency

Disord 2008; 33: 66–71.

11. Fibiger S, Peters H,

Touzet, BB, Neumann K. Therapy for persons who stutter: Eastern Europe and Latin America. In: 5th World Congress on

Fluency Disorders, 25-28th July; 2006, Dublin, Ireland.

12. NetQues Project. Network for Tuning Standards & Quality of Educational Program for

Speech Language Therapists in Europe

funded by

ERASMUSENWA Life Long Learning Programme [online]

2010-2013 [cited 2014]. Available from: http://www.Netques.eu/?page

_id=44

13. Georgieva D. Non-avoidance Group Therapy

with Adults Stutterers: Preliminary Results. CoDAS, J of Sociedade

Brasiliera de Fonoaudiologia; 2014; 26 (2): 112–120.

14. Andrews

G, Guitar B, & Howie P. Meta-analysis

of stuttering treatment. J Speech Hear Disord 1980;45: 287–307.

15. Cordes

AK, Ingham RJ. editors. Treatment efficacy for stuttering: a search for

empirical bases. San Diego:

Singular Publ. Group; 1998, 213–242.

16. Prins D, & Ingham R. Evidence-based treatment

and stuttering – historical perspective. J

Speech Lang & Hear Res

2009; 52: 254–263.

17. Thomas C, & Howell P. Assessing efficacy of

stuttering treatment. J Fluency Disord 2001;

26: 311–333.

18. Conture EG. Stuttering: Its nature, diagnosis,

and treatment. Needham Heights,

MA: Allyn and Bacon. 2001.

19. Johnson W. Stuttering and what you can do

about it. Danville, IL:

Interstate; 1961.

20. Riley GD. Stuttering

severity instrument (4th edition). Austin, Texas:

PRO-ED; 2009.

21. Yairi E & Ambrose N. A longitudinal

study of stuttering in children: A preliminary report. J Speech Hear Res

1992; 35: 755–760.

22. Chang SE, Erickson KI, Ambrose NG, Hasegawa-Johnson MA & Ludlow

CI. Brain anatomy differences in childhood stuttering. NeuroImage 2008; 39:

1333–1344.

|

|

23. Foundas

AL, Bollich

AM, Corey DM, Hurley, M, & Heilman, KM. Anomalous anatomy of

speech-language areas in adults with persistent developmental stuttering.

Neurology 2001; 57: 207–215.

24. Cooper

EB. Chronic perseverative stuttering syndrome: A

harmful or helpful construct? Am J Speech Lang Path 1993; 2(3):11–15.

25. Manning WH. Clinical decision making in fluency disorders

(3rd ed). Clifton Park,

New York: Delmar/Cengage

Learning. 2010.

26. Shapiro DA. Stuttering Intervention. A Collaborative

Journey to Fluency Freedom (2nd ed). Austin, Texas:

Pro-ed; 2011.

27. Sheehan

JG. Stuttering: Research and therapy. New York: Harper and

Row; 1970.

28. Van

Riper C. The nature of stuttering (2nd ed). Englewood Cliffs, New

Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1982.

29. Watson JB. Exploring the attitudes of adults who stutter,

J Com Disord 1995; 28: 143–164.

30. Craig A, Hancock K, Tran Y, & Craig M. Anxiety levels in people who stutter: A

randomized population study. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2003; 46: 1197–1206.

31. Klein JF & Hood SB. The impact of

stuttering on employment opportunities and job performance. J Fluency Disord 2004; 29(4): 255–273.

32. Brutten GJ & Shoemaker DJ. A two-factor

learning theory of stuttering. In Travis LE (Ed), Handbook of speech pathology

and audiology. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1971: 1035–1072.

33. Ornstein A & Manning W. Self-efficacy

scaling by adult stutterers. J Com Disor 1985; 18: 313–320.

34. Woolf G. The assessment of stuttering as

struggle, avoidance and expectancy. British J Disord Com 1967; 2: 158–171.

35. Wright

L, Ayre A. WASSP: Wright and Ayre Stuttering Self-rating Profile. Bicester:

Speechmark; 2000.

36. Ayre A, Wright L. WASSP: an international

review of its clinical application. Intern J

Speech Lang Path 2009;11(1): 83–90.

37. St Louis KO, Filatova Y, Coskun M, Topbas S, Ozdemir S, Georgieva D, McCaffrey E, George R. Public Attitudes Toward Cluttering and Stuttering

in Four Countries. Chapter in book “Psychology of Stereotypes”, Nova Science Publishers, Inc, New

York, 2011; 81-115.

38. Yaruss JS. Assessing

quality of life in stuttering treatment outcomes research. J

Fluency Disord 2010; 35: 190–202.

|

|

39. Craig A, Blumgart E, &

Tran Y. The impact of stuttering on the quality of life in adults who

stutter. J Fluency Disord 2009; 34 (2): 61–71.

40. Klompas M & Ross E. Life experience

of people who stutter, and the perceived impact of stuttering on quality of

life: Personal accounts of South African individuals. J Fluency Disord 2004;

29(4): 275–305.

41. St. Louis KO, Filatova Y, Coskun M, Topbas S, Ozdemir S, Georgieva D, McCaffrey E, George R.

Identification of cluttering and stuttering by the public in four countries.

Intern J Speech-Language Pathology;

2010;12 (6): 508–519.

42. IALP International Association of Logopedics and

Phoniatrics. Guidelines for initial education in logopedics (speech/language

pathology/ therapy, orthophony, etc.): Folia Phoniat Logop 1995; 47: 296–301.

43. IALP (2010) Education Guidelines (September 1, 2009): Revised

Guidelines for Initial Education in Speech-Language Pathology. Folia Phoniat Logop; 2010;62:210–216.

45. Van Riper C. The treatment of

stuttering. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1973.

46. Riley

G. Stuttering severity instrument for children and adults. 3rd

edition. Austin:

Pro-Ed; 1994.

|

|

47. Georgieva D. Acoustic and Electroglottographic Voice

Characteristics in Stuttering: Data From Two Cases. Proceedings of the 10th

International Conference on Advances in Quantitative

Laryngology, Voice and Speech Research, June 3-4, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. 2013a; 83–84.

48. Georgieva D. Acoustic and Electroglottographic Voice Characteristics in

Stuttering: Group Study. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Advances in Quantitative

Laryngology, Voice and Speech Research, June 3-4, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA; 2013b;

85–86.

49. Yaruss JS. Measuring multiple outcomes in

stuttering treatment. In: 7th

Oxford Dysfluency Conference, Oxford, 2005; 5–11.

50. Yaruss JS. Describing the consequences of

disorders: Stuttering and the International Classification of Impairment,

Disability, and Handicaps. J Speech Lang Hear Res 1998; 49, 249–257.

51. Andrews G, Cutler J. Stuttering

therapy: The relation between changes in symptom level and attitudes. J

Speech Hearing Disord; 1974, 34: 312–319.

52. Ornstein

A, Manning, W. Self-efficacy scaling by adult stutterers. J Com Disord

1985;18, 313–320.

53. Crowe

TA, Cooper EB. Clinician attitudes toward and knowledge of stuttering. J Com

Disord 1977;10: 343–357.

54. Yaruss JS, Quesal RW. Stuttering and the International

Classification of Impairment, Disability, and Health (ICF): An update. J Com

Disord 2004; 37: 35–52.

|

|

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment