Amy Marie GREENE

Clarion University

Northcentral University, USA

Recived: 27.08.2014

Accepted: 22.10.2014

Original article

Citation: Greene AM. Passing standardized assessments

with fading prompts. J Spec Educ Rehab 2015; 16(1-2): 68-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/JSER-2015-0005

Introduction

Through passing No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB), the United

States Federal Government mandated that states meet certain

requirements and develop state assessments to evaluate whether all

students are making progress to a level of proficiency. As a result of

NCLB, the members of the Pennsylvania Department of Education instituted

the Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA), which

evaluates writing based on prompts using a rubric. According to NCLB,

measurable yearly benchmarks, which are referred to as Adequate Yearly

Progress (AYP), must be set to ensure that 100% of students are

performing at a level of proficient by the 2013-2014 school year. The

supporters of NCLB mandate that all students, including those with

learning and intellectual disabilities, perform at a level of proficient

on grade level state assessments with only small group settings as an

accommodation (1–4).These students are expected to meet the same cut

score levels as their nondisabled grade level peers. (4) Students with

learning and intellectual disabilities are by nature at risk for not

meeting a level of proficient due to their common characteristics of

deficits in the areas of computation, strategy development, memory,

self-regulation, motivation, and generalization to state writing

assessments (5–7).

Proficiency on state assessments, such as the PSSA, is a concern

for administration, teachers, parents, and students. If AYP is not met

funding is reduced and government involvement is instilled within the

school districts at varying levels depending on the number of

consecutive years the goal is not met (2). Members of the IEP subgroup

who have a disability in the area being measured are clearly at a higher

risk for not performing at a level of proficiency (8). The issue of

passing statewide assessments, such as the PSSA, is becoming even more

important since some states already do not permit students who do not

pass the test to receive a diploma (9).

Although there has historically been a controversy between

advocates for cognitive and behavioral approaches to teaching, NCLB has

caused it to be even more pressing. Due to NCLB, teachers need to find

the most effective strategy for assisting students with disabilities in

passing state assessments. Directly teaching the skills through

behavioral techniques has been deemed successful for students with

learning and intellectual disabilities due to their common areas of

deficits (10–18). Although the research has shown behavioral approaches’

successfulness for students with learning and intellectual

disabilities, the advocates for cognitive approaches continue to

criticize behavioral approaches for being too rigid (11, 19).

A substantial amount of research on teaching writing over the last

several decades has been based on cognitive approaches, such as product,

process, and Self-Regulated Strategies Development (SRSD). A large

portion of this research was conducted by Graham (20) or replicated his

work. Early on Graham (20) has found difficulties in implementing

cognitive strategies for students with learning and intellectual

disabilities, which included deficits in composition, mechanics, and

motivation (20–23). A review of the 30 years of SRSD research allowed

researchers to find differences in strategies behavior, writing

skills, knowledge, and motivation that led to difficulties utilizing

this cognitive approach for students with learning and intellectual

disabilities (6). Of the quantity of research on SRSD, only five

experimental or quasi-experimental designs met the criteria for being

acceptable research, while only nine single-subject designs were deemed

of quality (24). None of the researchers who conducted studies on

cognitive strategies addressed generalization of these skills to

standards-based state assessments in writing.

Through reviewing the research on both cognitive and behavioral

approaches, it can be determined that a behavioral approach for

instruction in the use of strategies that provide explicit,

teacher-directed instruction for all levels of the writing process is an

essential component in teaching students with learning and intellectual

disabilities to learn to write and generalize these skills to a

proficient level on state assessments (7, 25). Although there are no

other studies specifically addressing Fading Prompts through Graphic Organizers

method (FPGO), due to the author creating the program, there is

substantial research on other behavioral approaches that utilize graphic

organizers. Researchers have found significant gains in writing for

students with learning and intellectual disabilities as measured by

Correct Word Sequencing (CWS), and the standardized TOWL-3, and

maintenance of these skills through the use of the behavioral

approach(16–18).

Due to NCLB there is a need for researchers to further address

generalization of learned skills to state assessments. Researchers found

that through the behavioral approach of fading prompts in graphic

organizers, three students with learning disabilities were able to

advance from below basic (1) to a level of proficient (3) on the PSSA,

while two did not pass the assessment; they did advanced from a score of

below basic (1) to basic (2) (26). Researchers found that all the

common characteristics of students with learning and intellectual

disabilities needed to be addressed in order to assist them in passing

state assessments (27–29). Researchers have also found that when

explicit instruction, such as utilized in a behavioral approach, is

provided to students with learning disabilities they can perform at the

same level as their nondisabled peers, maintain these skills over time,

and generalize these skills to state assessments (30). The purpose of

this quantitative study was to examine the performance scores on the

PSSA writing prompts assessment following FPGO as a treatment for

students with learning and intellectual disabilities by comparing

archived pretest, posttest, and actual PSSA results to determine if

significant differences existed. The participants’ PSSA results were

also compared to the average state PSSA results for the IEP subgroup. As

more is learned about the effectiveness of FPGO, schools may use this

information to assist students in passing state assessments in the area

of writing.

Materials and Method

The sample population was taken from a small town located in

northwestern Pennsylvania. The sample size included a total of 45

students, ranging in age from 13 to 18 years old, who were placed in the

learning support English setting by the IEP team in 8th or 11th

grade (PSSA testing grade levels) for the 2005-2010 school years. The

sampling included all students labeled with a learning disability in

writing or an intellectual disability who were exposed to FPGO

treatment, which was an inclusive group. In 2005-2006, the sample

included 7 students in the 8th grade. During 2006-2007, 7 students in the 11th grade were included. In 2007-2008, three 8th grade students were included and 11 students in 11th grade participated. In the 2008-2009 school year 7 students in the 11th grade were included. During the 2009-2010 school year 10 students in the 11th

grade were involved. The demographic characteristics of the 45 students

consisted of 34 students with a learning disability, which represents

76%, and eleven with an intellectual disability, which represents 24%.

Thirteen of the students were female, while 32 were male. Racially, 100%

of students were Caucasian, due to 99% of the population within the

school district being Caucasian.

The researcher utilized prompts selected from the PSSA writing

assessment preparation book and the PSSA scoring rubric, as well as the

results of the archived pretests, posttests, and the results of the

actual PSSA for the 2005-2010 school years. The pretest and posttest

results were determined through the use of the PSSA rubric as a

measurement instrument to determine if students’ writing was at a score

of 1- 4. The scale indicated below basic (1), basic (2), proficient (3),

or advanced (4), as adopted in 1999 by the members of the Pennsylvania

Department of Education. (31) A score of proficient or advanced is

considered a passing score. Reliability for the PSSA was addressed

through a stratified coefficient alpha, standard errors of measure

(SEM), conditional standard errors of measure (CSEM) with the Rasch,

decision consistency, and rater agreement. In regards to validity, the

PSSA addressed the following: (a) test content, (b) response processes,

(c) internal structure (d) the relationship between test scores and

other variables, (e) the consequences of testing. (31)

Prior to the implementation of the FPGO as a treatment, students

were presented with a PSSA writing prompt that was taken from a PSSA

preparation book, which included narrative, informative, and persuasive

prompts. Each student’s response was evaluated through the use of the

rubric that was utilized within FPGO in order to provide specific

feedback to students. The PSSA rubric was then utilized to derive a

score of below basic (1), basic (2), proficient (3), or advanced (4).

The scores were then reported as students’ baseline data due to the need

to have the pretest and posttest scores reflect the same assessment

tool, as the PSSA.

The teacher then utilized FPGO as classroom instruction. FPGO

provided a graphic organizer that contained twenty-five boxes

representing five paragraphs with at least five sentences in each. The

method results in completing a writing response that consists of an

introductory paragraph, three paragraphs as the body, and a closing

paragraph. Students were provided with the FPGO step 1, which contains

the most explicit set of prompts. As students became familiar with the

process, prompts were slowly removed and the students were presented

with FPGO step 2, which removes the names of the paragraphs, the

prompting for the introductory sentence, and names of the topic and

supporting sentences. When students reached a level of mastery, they

were given FPGO step 3, which faded the prompting by removing all

prompting through words, and left only numbers and letters. As skills

continued to develop, students were presented with FPGO step 4, which

provided them only empty boxes.

Once mastery of the skills had been met, students were provided

with three pieces of blank typing paper and were expected to develop the

graphic organizer independently by drawing the boxes. Having the

students create their own graphic organizers was essential due to PSSA

administration guidelines not allowing students any supplemental aids

other than blank paper. Students progressed through the fading prompts

steps at different speeds, but all students were expected to reach a

level of proficiency.

One writing prompt was completed weekly to ensure retention. After

exposure to FPGO and prior to the PSSA assessment, samples of the

students’ written responses were evaluated by the researcher and three

other trained teachers with the PSSA rubric. The teachers consistently

derived the same scores. These data were reported as posttest data. A

quantitative design was used to test if significant differences occurred

between performance scores on the PSSA writing assessment following

FPGO for students with learning and intellectual disabilities. The

archived data used in this study was the result of a manipulation of the

independent variable by presenting the extra stimulus of graphic

organizers.

Four dichotomies for percent differences were utilized to determine

if significant differences occurred in PSSA results after the

implementation of FPGO. The first dichotomy compared the teacher

administered pretests to the teacher administered posttests for the

2005-2010 school years. The second dichotomy compared the teacher

administered pretests to the actual PSSA results to determine if

differences existed. Rater reliability and generalization of the

learned skills by the students were then addressed through a dichotomy

of percent differences that compared the teacher administered posttests

to the actual PSSA results. The fourth dichotomy compared the PSSA state

administered local results for the students that received FPGO to the

average PSSA pass and non-pass rates for the entire state of

Pennsylvania’s IEP subgroups. Rater reliability was addressed through

having the researcher re-score pretest and posttest data at a later

time, having three other teachers also score the data, and comparing the

archived posttest scores to the actual PSSA scores. As indicated, the

PSSA rubric addresses reliability through a stratified coefficient

alpha, standard errors of measure (SEM), conditional standard errors of

measure (CSEM) with the Rasch, decision consistency, and rater agreement

and validity through (a) test content, (b) response processes, (c)

internal structure (d) the relationship between test scores and other

variables, (e) the consequences of testing. (31).

Results

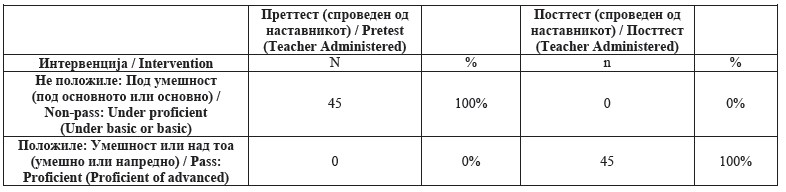

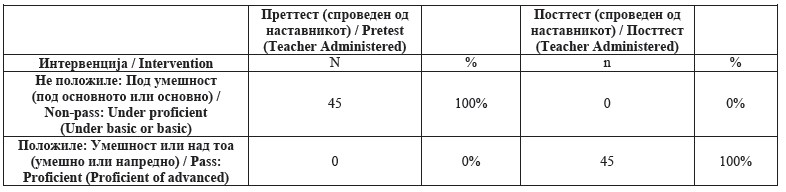

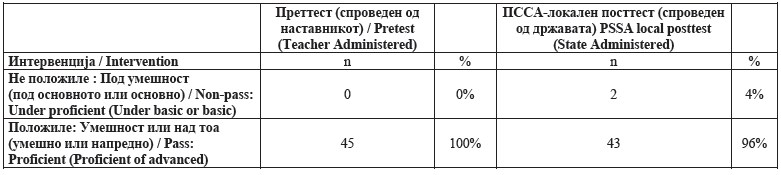

All 45 students received a below basic (1) on their archived pretest and

a proficient (3) score on their archived posttest. Forty-three students

earned a score of proficient (3) on the actual, archived PSSA

assessment; while two students received a score of basic (2) (see Table

1, for archived pretest, posttest, and PSSA scores). As indicated

earlier, the reliability and the validity of the actual PSSA assessment

were determined by the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

Table 1.Pretest, Posttest and PSSA results

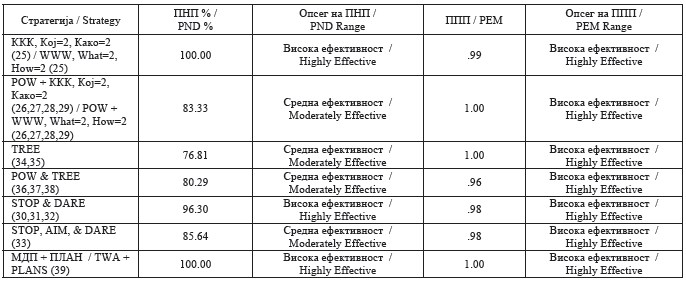

Four dichotomies for percent differences were carried out. The results

were calculated by subtracting the difference in percent between the two

columns in either row. The outcomes of the first dichotomy for percent

differences, which compared the percent of pass and non-pass rates when

comparing the teacher administered pretests and posttests for the

students with learning and intellectual disabilities that received FPGO

for the 2005-2010 school years, resulted in FPGO making a 100%

difference (100% - 0%=100%) in passing the PSSA, or not passing the PSSA

(see Table 2, for dichotomy for percent differences for the pretest and

posttest data).

Table 2.Dichotomy for percent differences in pretest and posttest data

Therefore, it was determined that FPGO was effective in assisting the

students with learning and intellectual disabilities in passing the

standards-based state assessment of the PSSA at a significance level of

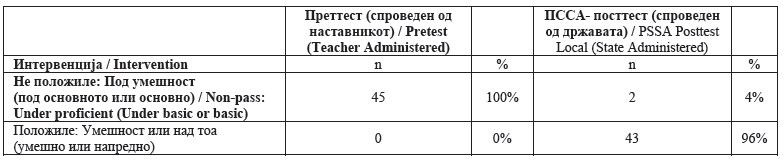

0.001, or 99.99% confidence level. The second dichotomy, which compared

the percent of pass and non-pass rates through comparing the teacher

administered pretests to the actual state administered PSSA, analysis

showed that FPGO made a 96% difference (100% - 4% = 96% and 96% - 0% =

96%) in passing the PSSA, or not (see Table 3, for dichotomy for percent

differences for pretest and PSSA data).

|

|

Table 3.Dichotomy for percent differences for pretests and PSSA data

|

|

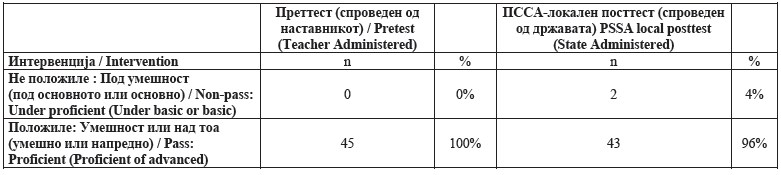

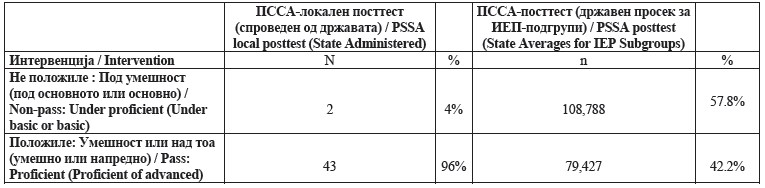

The third dichotomy, percent differences analysis, addressed the teacher

administered posttests and compared them to the actual state

administered PSSA results. The results found a 4% difference (4% - 0%=4%

and 100% - 96%=4%), which indicated rater reliability and

generalization of the learned skills by the students to the actual PSSA

(see Table 4, for the dichotomy for percent differences for posttest and

PSSA data).

Table 4.Dichotomy for percent differences for posttest and PSSA data

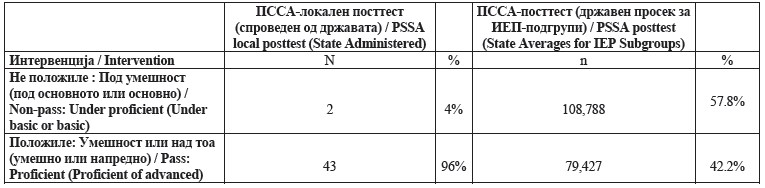

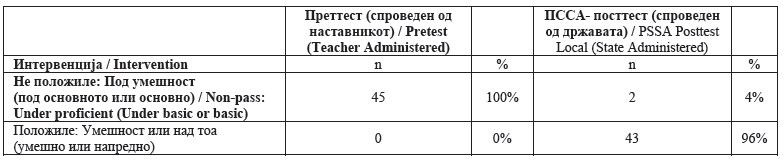

The fourth dichotomy compared the PSSA posttest state administered

local results for the students that received FPGO to the average PSSA

pass and non-pass rates of the entire state of Pennsylvania. The fourth

dichotomy resulted in FPGO making a 53.8% (57.8% - 4%=53.8% and 96% -

42.2%=53.8%) difference for students with IEPs, which indicates learning

and intellecttual disabilities, in passing the PSSA, or not (see Table

5, for dichotomy for percent differences for local and state PSSA data).

Table 5.Dichotomy for percent differences for the local and state PSSA data

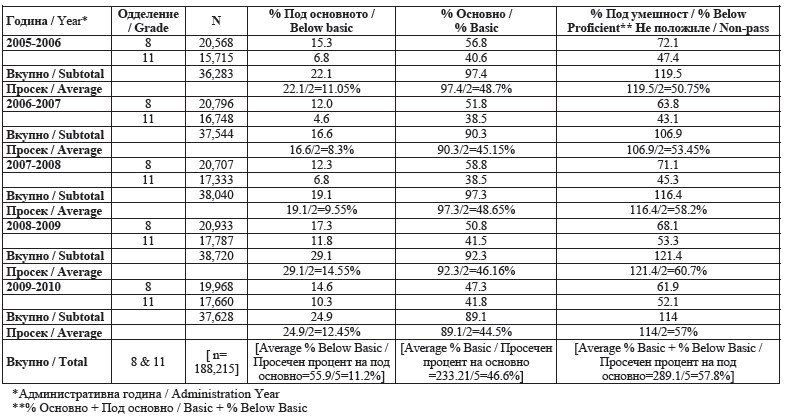

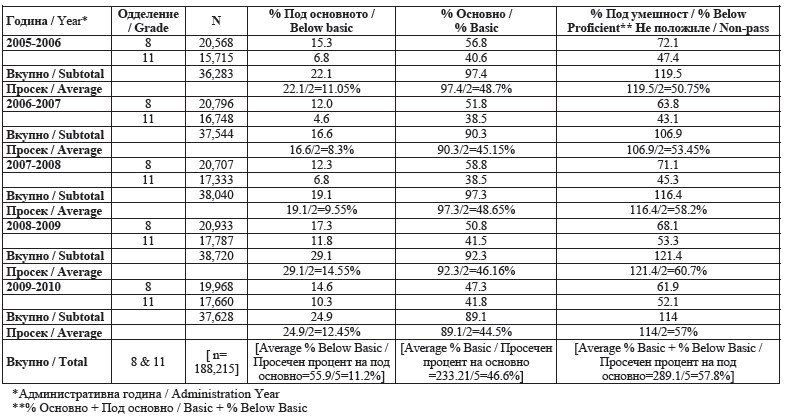

The PSSA data that were utilized to calculate the overall non-passing

percent for the entire state of Pennsylvania when addressing the IEP

subgroup was utilized in order to be the most reflective of the sample

addressed in this study. It is important to indicate that the state’s

IEP subgroup included all students with an IEP. Therefore, students that

did not have deficits in writing were included; while this study’s

sample addresses only students with an IEP reflecting deficits in

written expression. Of the 188.212 students with an IEP in the state of

Pennsylvania, 57.8% did not pass the PSSA (see Table 6, for PSSA data

utilized to calculate overall average non-passing percent).

Table 6. PSSA data utilized to calculate the overall average of non-passing percent

The PSSA data that were utilized to calculate the overall passing

percent for the entire state of Pennsylvania when addressing the IEP

subgroup, again reports all students with an IEP, not just students with

disabilities in written expression. Although this included students who

did not have deficits in writing, only 42.2% passed the PSSA (see Table

7, for PSSA data utilized to calculate overall average passing

percent).

\

Table 7. PSSA data utilized to calculate the overall average of passing percent

Based on the outcomes of the four dichotomies for percent, it was

determined that significant differences in performance scores on the

PSSA writing prompts assessment existed following FPGO treatment for

students with learning and intellectual disabilities through comparing

archived pretest, posttest, and actual PSSA results. It was further

determined that the outcomes of FPGO generalized to the PSSA.

Discussion

Although the supporters of NCLB have placed a great deal of

emphasis on performing at a level of proficient on state assessments, no

studies address the effectiveness of cognitive approaches generalizing

to state assessments, few studies have addressed the effectiveness of

behavioral approaches generalizing to state assessments, such as the

PSSA, and no other studies have addressed the use of FPGO. This research

provides additional insight into the effectiveness of behavioral

approaches to teaching writing, as well as addresses how effectively

these skills generalize to state assessments, such as the PSSA. Only 2

of the 45 students in this study did not pass the PSSA. However, both

students advanced from a score of below basic (1) to a score of basic

(2). It is also important to indicate that the 2 students who did not

pass were identified as having an intellectual disability. The current

review of literature excluded these students.

The major limitations within this study focus around the sampling

procedures and the research design. The sampling procedures were based

on accessibility and convenience and did not include random sampling.

True random sampling did not occur since the testing group was

established based on students being identified with a learning or

intellectual disability and placed in the learning support setting for

their English instruction by the IEP team and parent consent.

Convenience sampling led to including only students in one school

district, which resulted in all of the students within the sample

population being Caucasian. Given that the PSSA is only administered to

middle and high school students in 8th and 11th grades, the results of the FPGO were not tested on any other grade levels of students.

The structure of the study resulted in only one teacher

implementing FPGO treatment for teaching writing. Although this

controlled for treatment fidelity, which refers to following the exact

procedures specified by the researcher, this also leads to questioning

whether another teacher would have the same success with FPGO. It would

be beneficial to generalize the outcomes of this study to the entire

state of Pennsylvania in order to increase school districts’ AYP to

comply with NCLB; however, the lack of random sampling makes

generalization difficult. Comparing the local state administered PSSA

results to the entire state of Pennsylvania’s IEP subgroups’ non-pass

and pass percent also led to comparing students with disabilities in

writing at the local level to students that may not have a deficit in

writing in the state’s IEP subgroup.

There were further limitations due to the research design. In the

quasi-experimental research design, the researcher is attempting to

identify cause and effect by controlling the independent variable.

Although the research was collected over a span of several PSSA testing

years, limitations of not having a control group or returning to

baseline as a means of comparison make it difficult to insure that the

independent variable was controlled. The research design did not allow

for return to baseline due to the fact that the students would

automatically utilize the learned writing skills that were developed

during the treatment phase.

Further studies should address sampling limitations by conducting a

larger scale study to include several school districts from other

demographic areas. The inclusion of numerous school districts may also

be needed to create a stratified sample to represent other ethnic

groups. Additional studies should also address the effect of FPGO on

students in 7th, 9th, and 10th grades.

Further studies should also be conducted to address any structural

limitations within this study. Larger scaled studies should evaluate the

effectiveness of FPGO treatment when different teachers with varying

backgrounds implement the treatment. In order to further explore the

amount of control that was exhibited over the independent variable of

adding an extra stimulus of graphic organizers to the prompts,

additional research should be conducted to reflect the use of a control

group. The results of this program should be compared to other

strategies for teaching writing, such as cognitive approaches that are

currently being utilized.

Conclusion

Given that the only two students who did not pass the PSSA with a

score of proficient (3) were identified as having intellectual

disabilities, additional studies that compare students with learning

disabilities versus students with intellectual disabilities may provide

further insight into the effectiveness of the program. Additional

research should also be conducted on the effectiveness of FPGO treatment

with students who do not have disabilities. Based on the outcomes of

this study, which indicate that FPGO treatment led to significant

differences between performance scores on the PSSA writing assessment

for students with learning and intellectual disabilities, it is highly

recommended that this program be utilized at least for students with

learning and intellectual disabilities until further research can be

done.

Conflict of interests

Author declare that have no conflict of interests.

References

|

|

|

|

-

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107-110, § 115, Stat. 1425 (2002).

-

Yell ML. The law and special education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2006.

-

PSSA Coach. New York, NY: Triumph Learning; 2007.

-

Pennsylvania Department of Education. Accommodations guidelines:

PSSA [online]. 2010 [cited 2011 Mar 1]. Retrieved from: URL:http://www. education.state.pa.us/

-

Eisenmajer N, Ross N, Pratt C. Specificity and Characteristics of

learning disabilities. Journal of Child Psychology 2005;

46(10):1108–1115.

-

Graham S, Harris KR. Almost 30 years of writing research: making

sense of it all with the wrath of khan. Learning Disabilities Research

& Practice 2009; 24(2):58–68.

-

Hallahan DP, Kauffman JM. Exceptional learners: An introduction to special education. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2006.

-

Swain KD. Students with disabilities meeting the challenge of

high-stakes writing assessments. Education 2006; 4(126):660–665.

-

Yell ML, Katsiyannas A, Shiner JG. The no child left behind act,

adequate yearly progress, and students with disabilities. Teaching

Exceptional Children 2006; 4(38):32–39.

-

Ganz J, Flores M. The effectiveness of direct instruction for

teaching language to children with autism spectrum disorder: Identifying

materials. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2009;39:75−83.

-

Hang-Li Z. Investigation and analysis of current writing teaching

mode among English majors in normal universities in China. US-China

Education Review 2010; 8(7):22–27.

-

Kauffman JM, Hallahan DP. Special education: What it is and why we need it. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2005.

-

Martella R, Waldron-Soler K. Language for writing program evaluation. Journal of Direct Instruction 2005; 5(1):81–96.

-

Stebbins LB, Pierre RG, Proper EC, Anderson RB, Cerva TR.

Education as experimentation: A planned variation model. Cambridge: Abt

Associative; 1977.

-

Vitale M, Joseph B. Broadening the institutional value of direct

instruction implemented in a low-SES elementary school: Implications for

scale-up and school reform formal. Journal of Direct Instruction 2008;

8(1):1–18.

-

Walker BD, Shippen ME, Alberto P, Houchins DE, Cihak DF. Using the

expressive writing program to improve the writing skills of high school

students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research

& Practice 2005; 3(20);175–183.

-

Walker BD, Shippen ME, Alberto P, Houchins DE, Cihak DF. Using the

expressive writing program to improve the writing skills of high school

students with learning disabilities. Journal of Direct Instruction

2006; 6(1):35–47.

|

|

-

Walker BD, Shippen ME, Houchins DE, Cihak DF. Improving the

writing skills of high school students with learning disabilities using

the expressive writing program. International Journal of Special

Education 2007; 2(22):66–76.

-

Yi Y. Toward an eclectic framework for teaching EFL writing in a

chinese context. US-China Education Review 2010; 3(7):29–33.

-

Graham S. The role of production factors in learning disabled

students’ composition. Journal of Educational Psychology 1990;

82:781–791.

-

Graham S, Harris KR, MacArthur C, Schwartz S. Writing and writing

instruction with participants with learning disabilities: A review of a

program of research. Learning Disabilities Quarterly 1991; 14:89–114.

-

Morris NT, Crump DT. Syntactic and vocabulary development in the

written language of learning disabled and non-disabled participants at

four age levels. Learning Disabilities Quarterly 1982; 5:63–172.

-

Thomas C, Englert C, Gregg S. An analysis of errors and strategies

in the expository writing of learning disabled participants. Remedial

and Special Education 1987; 8(46):21–30.

-

Baker SK, Chard DJ, Ketterlin-Geller LR, Apichatabutra C, Doabler

C. Teaching writing to at-risk students: The quality of evidence for

self-regulated strategy development. Exceptional Children 2009;

3(75):303–319.

-

Troia G, Graham S. The effectiveness of a highly explicit,

teacher-directed strategy instruction routine: Changing the writing

performance of participants with learning disabilities. Journal of

Learning Disabilities 2002; 35:290–305.

-

Deatline-Buchman A, Jitendra AK. Enhancing argumentative essay

writing of fourth-grade students with learning disabilities. Learning

Disabilities Quarterly 2006; (29): 39–54.

-

Garcia-Sanchez JN, Fidalgo-Redondo R. Effects of two types of

self-regulatory instruction programs on students with learning

disabilities in writing products, processes, and self-efficacy. Learning

Disabilities Quarterly 2006; 3(29):181–211.

-

Graham S, Perin D. A meta-analysis of writing instruction for

adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology 2007; 99:445–476.

-

Monroe BW, Troia GA. Teaching writing strategies to middle school

students with disabilities. Journal of Educational Research 2006;

1(100):21–33.

-

Schumaker JB, Deshler DD. Adolescents with learning disabilities

as writers: Are we selling them short? Learning Disabilities Research

& Practice 2009; 24(2):81–92.

-

Pennsylvania Department of Education. The 2009 PSSA writing state

level proficiency results. [online] 2009 [cited 2010 June 1] Retrieved

from: URL:http://www.education. state.pa.us/

|

/images/85-104.miksaj-todorovic-tabela1.jpg)

/images/85-104.miksaj-todorovic-tabela2.jpg)

/images/85-104.miksaj-todorovic-tabela3.jpg)

/images/85-104.miksaj-todorovic-tabela4.jpg)

/images/85-104.miksaj-todorovic-tabela5.jpg)

/images/85-104.miksaj-todorovic-tabela6.jpg)